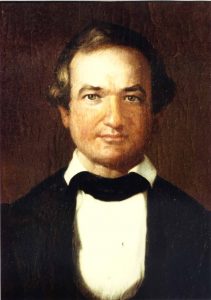

JOHN HARDIE

1796 – 1848

John Hardie of Thornhill was baptized on 6 March 1796 in Saline, Fifeshire, Scotland. John Hardie left Scotland by ship from Leith, the port of Edinburgh, and arrived in New York on July 18, 1817. After another voyage of eleven days from New York, he arrived on August 6, 1817, in Richmond, Virginia, where he worked for a year. While he was working out his contract in Richmond, David Ireland, a friend from Scotland, wrote to John about Huntsville, Alabama. Ireland had taken a ship from New York to Mobile and then a boat up the river to Huntsville, a journey more easily said than done in 1817. According to John’s letter home, Ireland wrote: “Last year about this time, there was not a house except a hut or two, and now it contains three stores.” Evidently this sufficiently whetted John’s appetite because in September 1818 he and a friend, James Black, set out overland from Richmond with a horse-drawn wagon. They arrived in Huntsville 24 days later on October 19, 1818.

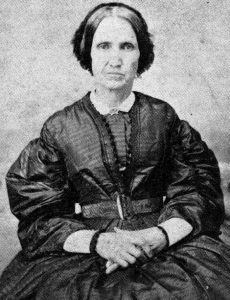

MARY MEAD HALL HARDIE

1812 – 1872

According to Lillian Martin’s book, John Hardie of Thornhill and His Family, Mary Mead Hall was born on October 19, 1812, in Suffolk, Virginia. Mary’s mother was also named Mary and her family name was Mead, according to most sources, but we have no further information about her mother’s origins. Mary’s father was Isaac Hall, a Methodist minister, whose origins are equally unknown. Mary was ten years old when her family moved to Florence, Alabama, in 1822, about four years after John Hardie moved from Richmond, Virginia, to Huntsville, Alabama. The Hall family included six children when they left Virginia for north Alabama. Elizabeth was twenty-five years old, Martha was twenty-two, Isaac was fourteen, Sarah was twelve and Joshua was eight.

The Tennessee river valley in Alabama was contested by Indians at the end of the eighteenth century, but it was opened to settlers when John Hunt of Virginia settled Huntsville in 1805. In 1813 congress claimed that the present state of Alabama was included in the Louisiana purchase, and it became subject to the jurisdiction of the United States for the first time. The Creeks in Alabama were hostile to the whites who were encroaching on their traditional hunting lands, and it was not until 1814 that the danger from Indians was eliminated. Alabama became a state in 1819. Clearly the Halls were bringing their young family to the frontier.

The last Hall child, James, was born after the move to Florence, and he died in infancy in Florence in August 1824. The remaining Hall children were orphaned when their mother died in 1824 and their father died in 1825. Mary at age thirteen and her sister Sarah, who then was fifteen, went to live with their older sister Martha and Martha’s husband Joshua Willis in Triana, Alabama.

In 1828 Joshua Willis introduced his sister-in-law Mary to John Hardie. She was only sixteen, and John was thirty-two. One imagines that Joshua and Martha were happy to have a burden lifted, and Mary was probably as happy to be away from her sisters. In any event, we know of no objections to the marriage based on the difference in their ages. They were married on November 28, 1828, in Triana which is ten miles down river (west) from Whitesburg where John Hardie and his partner James White had operated their store since 1820. John and Mary set up housekeeping in Whitesburg, and their first child, John Timmons Hardie, was born a year later on November 29, 1829.

Whitesburg (originally Ditto’s Landing) was located in Madison County, Alabama, and was one of many landings and trading posts along the Tennessee river in Alabama. Triana and Whitesburg remain as a small towns on Wheeler lake in the southwest corner of Madison County, Alabama.

Two more Hardie children were born at Whitesburg: James White on May 19, 1931, and Joseph on June 26, 1833. It’s hard to imagine what their life in Whitesburg was like. John’s partner went to Virginia each year to buy the stock for their store, but John and Mary seem never to have left.

It has been difficult to recreate their life in early Alabama because the letters that John Hardie wrote to his family back in Scotland reveal few details. We now have a source for details of their life on the frontier. The Louisiana State University Press has published a book by Daniel S. Dupre entitled Transforming the Cotton Frontier: Madison County, Alabama 1800 1840 that gives a thorough history of the region and brings to life in vivid detail the world in which John Hardie and his wife began their family. Unlike most states, Alabama was settled from two directions: first from the south and then from the north. Mobile was settled in the early 18th century and this coastal strip along the Gulf of Mexico remained separate from the northern part of the region. In the treaty of Paris of 1783 England ceded the land north of the coastal strip to the United States. The French revolution and the Napoleonic wars gave the United States an opportunity to acquire the rest of the lands that were held by the European powers. By the treaty of Madrid in 1795 Spain ceded its claims to the land east of the Mississippi, except the coastal strip, and in 1798 the region between the Mississippi and Chattahoochee rivers was organized by congress into the Mississippi territory. In 1813 congress annexed the coastal strip, as part of the Louisiana purchase, to the Mississippi territory, and in 1817 the region was divided into the state of Mississippi and the territory of Alabama. Alabama did not become a state until 1819. Although the United States claimed sovereignty over this territory, the Chickasaw and Cherokee Indian nations claimed ownership of most of the area as their traditional hunting lands.

Meanwhile, in 1804, John Hunt moved into the fertile land in the great bend of the Tennessee river. He founded Huntsville at the location of a sixty foot bluff overlooking the spring that feeds Indian creek flowing to the Tennessee river at what would become the village of Triana. Hunts’ family, the families of Joseph and Isaac Criner, and Old Man Ditto, who lived on the Tennessee river, were the only Europeans in the area. In 1806 the Chickasaw and Cherokee nations ceded to the federal government the land that became Madison County. The county is bordered on the north by Tennessee and on the south by the Tennessee river. The land on either side remained in the possession of the Indian tribes.

By 1809 about two thousand white settlers lived in Madison County as squatters. The land was not officially sold by the federal government until 1809 when approximately 24,000 acres were auctioned off. By the fall of 1811, when the land office was moved to Huntsville, over 126,000 acres had been sold, leaving over 196,000 acres in federal hands. The next big land sale was in 1818, and Dupre calls it “one of the greatest speculative booms in frontier history.”

Dupre cites John Hardie’s letters home as evidence of the settlers’ enthusiasm. John arrived in Huntsville with $500 dollars that he had evidently saved while working in Richmond, and he immediately wrote home for more. It’s not clear whether he used the money to buy land or to lend to others for that purpose. Interest rates were very high, and lenders could charge almost 40% to land speculators who expected to earn much more. The federal government sold the land in minimum tracts of 160 acres (a quarter section) at an average price of about $7.50 per acre. If he bought land during the boom, he must have bought it in smaller lots during the secondary trading.

According to his letters, quoted in Lillian Martin’s book, John Hardie of Thornhill and His Family, John began working on a six month’s contract as a clerk in John Read’s store. Read was also the manager of the land office. John later invested in a store with his friend James Black, and ultimately, in 1820, he moved to Ditto’s Landing on the Tennessee where he started a store called White and Hardie, in partnership with John Read and James White.

In 1822, the year that Mary Mead Hall’s family moved to Alabama, the store was prospering, trading in merchant goods and cotton. By 1825, Read had left the business and Ditto’s Landing had become Whitesburg, named for John’s partner. It was also the year that Mary Mead Hall moved to Triana, a few miles down the river from Whitesburg. A mortgage in favor of John Hardie in 1832 describes his business as “James White and John Hardie merchants & partners trading under the firm of John Hardie & Co.”

John Hardie must also have been investing in land. The early records of the land titles of Madison County can be found in the archives of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, but it’s not clear how reliable they are. On November 12, 1825, John Hardie took a mortgage from Michael Ditto on a quarter section to secure a debt of $863.96. The land title records do not show any purchases prior to 1826 when they show the purchase and sale of the same 100 acres along the Tennessee river. On May 3, 1826 (it wasn’t recorded until 1832) John Hardie purchased the property for $600 from David and Malinda Bellew, and on August 5, 1826, he sold it to William Cloud for $125. If these deeds recite the actual consideration (and they may not), John Hardie experienced a significant loss on the transaction.

Two years after his marriage to Mary, on December 3, 1830, John Hardie purchased lot 14 in the city of Triana from the trustees of the city. It is described as 99 feet on the east side of B street with its back to Water street. His purpose in buying the lot is not known because he and Mary continued to live in Whitesburg where their first three children were born in 1829, 1831 and 1833. During the early months of 1832, according to the records, John Hardie acquired an interest in about 319 acres in section 13, township 5, range 1 west, in a series of deeds from the owners of undivided fractional shares (which usually means they were heirs of the original owner). This land is on both sides of Indian creek about two miles from Triana. It is now within the boundary of the Redstone Arsenal, and part of the land is within the Wheeler National Wildlife Refuge. It must have been beautiful creek bottom land, ideal for farming. He later sold this property to Nathaniel Snoddy for about twice what he paid for it, according to the consideration recited in the deeds.

In December 1833, John Hardie and Solomon Spence (there is no indication that he is related to William Spence who married John Hardie’s sister Helen in Scotland in 1825) purchased 120 acres along the Tennessee river from John Timmons for $500. This purchase is inconsistent with John Hardie’s apparent liquidation of his holdings beginning in 1833.

On November 12, 1833, John Hardie and Mary Mead Hall Hardie executed a deed to William Cloud for 240.33 acres in several locations near Clarksville Landing between Flint river and the Tennessee river for a recited consideration of $500. The title records don’t show when he bought the land which is about seven miles east of Whitesburg. In April 1834 John and his wife executed the deed to sell the land in section 13 to Nathaniel Snoddy. And according to the deed, they “personally appeared” before the notary on July 9, 1834, to execute a deed selling 40 acres on Barren Fork creek for $50 to Henry B. Turner. That is the last transaction in Madison County. Soon thereafter John Hardie settled up with his partner, James White, and the family moved to Talladega County.

John Hardie’s correspondence with his family in Scotland doesn’t explain why he decided to leave Madison County. In fact, he seems to have wound up his affairs in Madison County with the original intent of returning to Scotland to visit his parents. In any event, the title records of Talladega County show that John Hardie’s first purchase of land in Talladega County was the east half of section 7, township 19, range 5 east which he purchased from Patrick H. Brown on October 13, 1835 for $800. This half section, about 320 acres, is located to the west of present state highway 21, and it is the land on which Thornhill was built.

John and Mary Hardie’s life and prosperity in Madison County can really be appreciated only in the context of the national and local economy. In his book, Professor Dupre lays out all the intricacies of contemporary finance and their effect on the settlers. Unfortunately, the title records give only the barest outline of John Hardie’s land transactions. Was he caught up in the speculative fever of the 1818 bubble that burst in the “panic of 1819”? Did he really experience a loss on his land dealings, or were they successful? John Hardie’s family was in Talladega by the time of the “panic of 1837”, but it was preceded by several years of significant economic disruption. How did these events influence John Hardie’s decision to leave merchant trading and take up farming? Most likely, John Hardie’s general caution kept him out of truly risky speculation, and his decision to move was a genuine interest in farming.

Mary was not yet twenty-four years old when she and John and their three children moved to Talladega County in 1835. Talladega County was created in 1832 with land purchased from the Creeks. John and Mary started with about 700 acres and lived in a small house while “Thornhill” was being built. The farm grew in time to 1700 acres. As Lillian Martin explains in John Hardie of Thornhill and His Family:

So we see that in 1835 John Hardie became a large land owner and a planter. On his plantation his “money crop” must have been cotton, but he also raised vegetables, beef, pigs, poultry, to feed all of the fifty to sixty people who lived on the plantation. All of the milk, eggs, and butter used at Thornhill were produced there. All of the articles of clothing for the family and for the fifty slaves were spun, woven, and sewn into garments there.

Yes, slaves. For John Hardie, the pious Scotch Presbyterian who had abhorred the idea of slave holding, had found no other satisfactory source of labor, and he became the owner of fifty human beings. John Hardie also set up a store in Mardisville, a town about a mile and a half south of Thornhill on the Sylacauga road.

Mary Hardie’s sister Martha Hall married Joshua Willis who died on December 7, 1835. Martha herself died in 1836 less than a year after her husband’s death, so Mary took in three of their children: Cornelia, Persia and Demetrius “D” Willis.

D Willis left Thornhill around 1845 to live in Texas with his uncle, and Mary’s brother, Isaac W. Hall. D Willis fought in the Mexican war and moved to Livingston, Texas, to live on land granted to veterans of the war. D Willis also served in 20th Infantry, CSA from 1862 until the end of the Civil War. As related in Lillian Martin’s book, John Hardie of Thornhill and His Family, Cornelia and Persia Willis lived at Thornhill until they were married. Cornelia married John Tyler Morgan who had organized the Alabama 51st Cavalry Regiment, Partisan Rangers, in which Alva Finley Hardie served after September 1862. After the war, Morgan served in the U.S. Senate. Persia married Aaron Levisee and lived in Shreveport, Louisiana, until her death.

Another of the Willis children, Leonidas “Lee” Willis, was raised in New Orleans, and he may have come back to Talladega to work as a clerk in the Hardie’s store in Mardisville. When John T. Hardie closed the store and moved to New Orleans in 1853, Lee left for Texas to live near his brother D. During the Civil War Lee Willis served in the Willis Cavalry Battalion of Waul’s Texas Legion from 1862 until the fall of Vicksburg; he then served on the staff of Nathan Bedford Forrest. After the war Lee moved to Salem, Oregon, where he died in 1899. Octavia grew up under the care of her aunt Sarah Hall Finley who was Mary Mead Hardie’s sister. Sarah Finley was married to Alva Finley, from whom John and Mary Mead Hardie took the name of their seventh child, Alva Finley Hardie.

The household also increased as John and Mary had more of their own children: Belle on November 5, 1835; Rob on February 7, 1838; Willie on December 9, 1840; Alva on April 10, 1844; Annie Eliza on July 6, 1846; and Tommie on January 10, 1849.

Can we really imagine the life during those years? Idyllic, perhaps, to one influenced by Rousseau’s image of nature. There were cycles of planting and harvest with inevitable anxieties about the weather. A late freeze might destroy fruit trees; a dry spell might stunt corn or cotton. Animals were bred, raised and butchered. The winters were cold with very little heating; the summers were hot with no cooling. Sickness must have been frightening.

A real sense of this life can be found in “Fear God and Walk Humbly”: The Agricultural Journal of James Mallory, 1843-1877, edited by Grady McWhiney, Warner O. Moore, Jr. and Robert F. Pace. Mallory was a planter in Talladega County, and the life he describes in his journal was very much the same as life on Thornhill farm. Indeed, the Hardies were well known to Mallory; his daughter, Elizabeth Darby (Lizzie) Mallory married Alva Finley Hardie, and the Hardies are often mentioned in his journal.

After thirteen years together at Thornhill, Mary’s husband, John, died. Mary was thirty-five years old and pregnant with their ninth child, and her oldest child was only eighteen. Nevertheless, she had no choice but to assume full responsibility for the family. John Hardie’s sister Helen and her husband and their five children moved to Talladega County in the fall of 1848, only a few months after John’s death. Mary’s sister Sarah, who had moved to Talladega County in 1845 after her first husband’s death, married the Reverend Oliver Welch in October. Then in January 1849 Sarah’s daughter Mary was married in Talladega. Tommie was born less than two weeks later. Would these events have been any less a strain on Mary then than they would be on a young widow today?

Mary not only survived these events, but she managed the farm and store and supervised the education of her children until they left home. James was the first to leave; he married in May 1851 and went to live in Jackson County, Alabama, in the northeast corner of the state. John T. left home for New Orleans in the spring of 1853 at age 23 after settling up the store in Mardisville. Joseph was away at college (first the University of Alabama and then Princeton) between 1850 and his graduation in 1855, and he then moved to Selma where he was married two years later. Belle was only twelve when her father died, but she was probably called on to help until she and Taul Bradford were married at Thornhill in February 1856. They lived in Talladega where they started their own family a year later. Willie left home for New Orleans in 1858 when he was seventeen years old. Rob, who was older than Willie, evidently stayed home with the younger children, Alva, Annie Eliza, and Tommie.

We know nothing of Mary’s feelings when the Civil War began in April 1861, but it shouldn’t be too hard to imagine that she was unhappy to see six of her sons join the Confederate army. She was left at home with Tommie and Annie Eliza. Belle and her children were also in Talladega, possibly at Thornhill for the duration of the war. James was also at Thornhill recovering from his wounds after the battle of Rocky Face ridge in May 1864.

We are ignorant of the relationship between master and slave at Thornhill, but we do know from contemporary sources that there was a general fear in the South that the slaves would rebel during the Civil War, especially after the Emancipation Proclamation. Therefore, it’s not hard to imagine the anxiety at Thornhill throughout the war as Mary worried about her children and tried to fulfill the Confederacy’s demands for food, horses, and other commissary supplies. Everyone in the Talladega valley suffered privation during the war. Most farms were shorthanded because their slaves were impressed for government services like the construction of fortifications at Mobile. Toward the end of the war, Talladega was invaded by Union cavalry raiders. “They fed their horses at Mrs. Hardie’s and consumed a large quantity of her oats, corn, bacon, etc.” according to a contemporary newspaper quoted by Lillian Martin.

After the war nothing would ever be the same. Mary Hardie found it necessary to lease the land surrounding Thornhill rather than try to farm it herself. She explained her predicament to John Hardie’s brother William in Scotland:

The farm is leased out to a farmer. I could not manage it myself now since the negroes are free. I have the dwelling house, yard, garden, & orchard. One of my old servants stays here when we go away and she takes care of everything. She was a slave but is so much attached to me & my children that she has no wish to leave us. I know that you all think slavery a dreadful thing, but there are thousands that were once well and happy that are now dying of want.

In a letter to Joseph and his wife Maggie, Mary shows still more cynicism about the situation created by Reconstruction:

The Darkees have become dissatisfied, they all expected to get rich this year, and they are just beginning to find that they were mistaken in their calculations. They supposed they were to have all the corn but 100 bushels. John Walker has become disgusted with farming & come to Taul to hire him for next year.

By 1868 Tommie was off at college, and Mary lived alone at Thornhill after Annie Eliza’s marriage in November 1869. Mary enjoyed a level of prosperity most survivors of the war could not match. She visited her children, and they visited her at Thornhill. She was in New Orleans for the birth of Annie Eliza’s first child in December 1871, and she returned to Thornhill in time for the birth of Belle’s eighth child on January 30, 1872.

Over the years, family letters often spoke of an illness, and Mary wrote of coughing in church, so it is likely that she suffered from tuberculosis. Evidently she was aware that her death was near, for all of her children were at Thornhill when she died on February 18, 1872, at age 59. She had outlived her husband by almost twenty-five years, and in that period she had raised their nine children, managed the farm and endured the crushing destruction of the Civil War. She was survived by all of her children and nineteen grandchildren. There are now over 700 living descendants of Mary Mead Hardie. She was a remarkable woman who was aptly described in eulogy by her minister as “modest, meek, unassuming, yet self-possessed, conscientious and firm.”